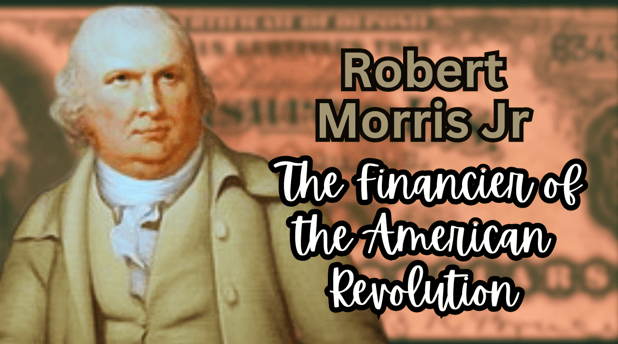

Robert Morris Jr.: The Financier of the American Revolution

Robert Morris Jr. (January 20, 1734 – May 8, 1806) was a pivotal figure in the founding of the United States, earning the title "Financier of the Revolution" for his critical role in supporting the Continental Army during the Revolutionary War. An English-born merchant, investor, and politician, Morris’s contributions spanned his work as a member of the Pennsylvania legislature, the Second Continental Congress, and the U.S. Senate. He holds the distinction of being one of only two people to sign the Declaration of Independence, the Articles of Confederation, and the U.S. Constitution, the other being Roger Sherman. Morris, alongside Alexander Hamilton and Albert Gallatin, is celebrated as one of the architects of the U.S. financial system.

Casey Adams

2/12/20253 min read

Early Life and Rise to Prominence

Born in Liverpool, England, Robert Morris was brought to North America at the age of 13 by his father, who sought opportunities in the colonies.

Settling in Philadelphia, Morris apprenticed with the prominent shipping firm of Charles Willing.

By the early 1760s, he had become a partner in Willing & Morris, one of the most successful mercantile firms in Philadelphia.

As Morris grew wealthier, his influence expanded.

By 1775, he was considered the richest man in America, amassing his fortune through trade and shipping.

However, the imposition of British taxation following the French and Indian War sparked Morris’s political engagement.

Like many colonial merchants, he opposed measures such as the Stamp Act of 1765, which he viewed as an overreach of British authority.

Role in the American Revolution

Supporting the War Effort

When the American Revolution began, Morris aligned with the Patriot cause.

In 1775, he was elected to the Second Continental Congress, where his financial acumen became indispensable. He served on critical committees, including:

The Secret Committee of Trade: Procured arms and ammunition for the Continental Army.

The Committee of Correspondence: Managed foreign diplomacy to secure international support.

The Marine Committee: Supervised the nascent Continental Navy.

Despite his contributions, Morris faced criticism for continuing some business dealings with British merchants early in the war, a practice he justified as a means to fund the revolution.

In 1778, he resigned from Congress to focus on his business but remained influential in Pennsylvania politics.

Superintendent of Finance

By 1781, the Revolutionary War had plunged the nascent government into a financial crisis.

Congress created the position of Superintendent of Finance to address the dire situation, and Morris was appointed to the role.

His tenure from 1781 to 1784 was marked by transformative initiatives, including:

Funding the Army: Working with financier Haym Salomon, Morris secured funds to support the Continental Army’s decisive victory at Yorktown.

Government Reforms: He streamlined procurement processes and reduced waste, making government operations more efficient.

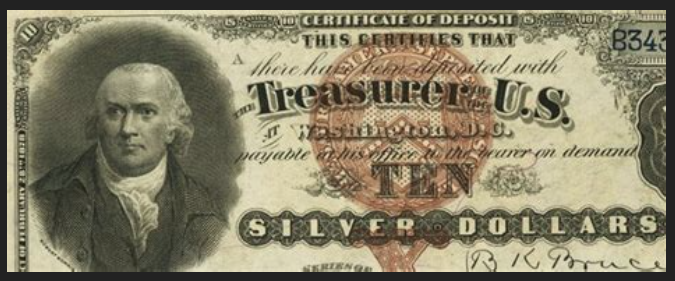

Establishing the Bank of North America: Chartered in 1781, this was the first national bank in U.S. history, providing much-needed credit to the government.

Morris also advocated for stronger federal powers, particularly the authority to levy taxes.

However, his efforts to amend the Articles of Confederation were stymied by the requirement for unanimous state approval, leaving the national government weak and financially unstable.

Contribution to the U.S. Constitution

Frustrated by the inefficacy of the Articles of Confederation, Morris was a key participant in the 1787 Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia.

Although he rarely spoke during the debates, his vision for a strong central government and sound financial policies influenced the resulting Constitution.

Morris worked behind the scenes to secure Pennsylvania’s ratification of the document, and by 1788, it had been adopted by the requisite number of states.

Service in the U.S. Senate

Morris was elected as one of Pennsylvania’s first two U.S. Senators when the new government was established.

He declined George Washington’s offer to become the nation’s first Treasury Secretary and recommended his close ally Alexander Hamilton instead.

In the Senate, Morris supported Hamilton’s economic program, which included creating a national bank, assuming state debts, and implementing tariffs to foster domestic industry.

His alignment with the Federalist Party underscored his belief in a robust federal government.

Financial Downfall

Despite his successes, Morris’s later life was marred by financial ruin.

He speculated heavily in land, amassing vast holdings but overextending his resources.

The Panic of 1796–1797 devastated his investments, leaving him unable to pay his creditors.

From 1798 to 1801, Morris was confined to the Prune Street debtor’s apartment adjacent to Walnut Street Prison in Philadelphia.

His imprisonment marked a tragic fall from grace for one of the nation’s wealthiest and most influential figures.

Legacy

After his release from prison in 1801, Morris lived quietly in a modest Philadelphia home until he died in 1806.

Though his financial missteps overshadowed his later years, Morris’s contributions to the founding and financial stabilization of the United States remain his enduring legacy.

Historians regard him as a visionary who laid the groundwork for the nation’s economic system.

His efforts during the Revolutionary War ensured the survival of the Continental Army, and his work as Superintendent of Finance and founder of the Bank of North America demonstrated the power of innovative financial solutions in times of crisis.

As a Founding Father who signed all three of the nation's founding documents, Robert Morris Jr. stands as a symbol of both the promise and the challenges of the American experiment.

Robert Morris Jr.